The year, despite its excrescences, provided a wealth of good picture books, and trying to keep up my level of reading from 2015, I managed to absorb forty-eight of them. I found plenty to recommend. You'll notice that my list and the Caldecott awards are entirely different as I've yet to read a single one of theirs, but I’ll write about that later on.

Firstly, I’ll reiterate myself from this time last year on what I consider to be a picture book:

"a book where words and images are used in combination and images contribute as much as or more than any text. Also, where the subdivision of pages into panels is not the dominant form"While I've attempted to place a division here between picture books and comics, because I believe they are ultimately different forms, I accept this may be artificial as there is certainly bleed-through. In this list, you will find that Professor Astro Cat, Kings of the Castle, King Baby, Owl Bat Bat Owl, The Wolves of Currumpaw, Pandora and There Is A Tribe of Kids all have comics sections or elements of comics language. To me, these elements are set within the framework of a picture book.

I'd also quickly like to state that I haven't been reading these with a child, so I'm coming from an adult's perspective, and appropriately start with:

Bum Bum by Taro Miura (Walker Books)

Simple in its design and humour, Bum Bum is perfectly formed and full of character. It builds with repetition to a satisfying conclusion and invites play, observation of contrasts and physical self-awareness. I'm happy to recommend it to readers of any age, but, please note, its effectiveness will rely on how funny you find this:

Professor Astro Cat's Atomic Adventure by Dr. Dominic Walliman and Ben Newman (Flying Eye Books)

This may be misplaced, but I'm very proud to have a non-fiction title in my line-up I can champion with the same enthusiasm as a fiction one. I think in Professor Astro Cat's case, this is because the narrative sense it shows is as strong, being loose overall but specific within each subject. The book is a capable primer in the basic principles of physics that is crammed with textual and visual detail, as you will see from the spread below.

All pages are subdivided in some way, but the page design, in this

1950's print style, always works and there is a colourful cast of

anthropomorphic animals to demonstrate practical examples of all the

concepts described. They have own relationships and a sense of belonging

to their own specific world. I'd highly recommend this one as a fun

read independent of its educational content.

Shy by Deborah Freedman (Viking)

Shy is the story of Shy, who hides in books and would love to make a friend. In form, it is fascinating and inventive, because Shy is literally hiding in the book.

This creates a very unusual tension, which relies on some figurative work but mainly abstract landscapes and pure colour to convey action and emotion. When the main character does finally appear, he is surrounded by others and unidentified, until the extraordinary moment when he appears from the spine of the book and you realise he had been there all along. The visual depiction of birdsong is also a brave choice and an effective one. In an original way, all these visual devices tie up the themes of shyness, hiding, being unidentifiable in a crowd and finding a voice. The effect is unique, and I hope Deborah Freedman continues to explore these new, conceptual territories in future books. A marvellous experience.

Already a firm favourite of mine, I have to say that some of Jeannie Baker’s very best work as a collager/illustrator has gone into this book. Overflowing with colour, texture and life, this book details the migratory journey of the godwit and on this framework hangs a lot of almost implicit drama; the loss of the chicks to a wolf in one page, the story of a boy in a wheelchair as the framing device. The sensitivity to colour in the book I find extremely beautiful, especially in the South-East Asia pages. The combination of natural and man-made materials in the collages, the luminousness and sense of environment that are achieved, are supremely skillful and give the story a quality of liveliness that's pretty much unique in picture books. The inclusion of the curvature of the earth throughout the book creates some wonderful perspectives, and crafts the idea of circularity visually. Like many of the books I'm writing about here, Circle appears simple and direct, but is a story of many layers.

Kings of the Castle by Victoria Turnbull (Templar Publishing)

A seemingly simple story of friendship, (mis)communication and imagination, set on a beach, Kings of the Castle is wonderfully constructed. It's perfectly paced, seamlessly slipping in and out of visual and verbal storytelling, picture book and comics language and a fold-out quadruple-page spread. Victoria Turnbull has an amazing sensitivity to colour, form, line and character that spins a wealth of meaning from a deceptively simple plot. I would have said at this point that I'd be dedicated to following her future work, has she not already delivered another, even greater book I'll be writing about in a moment.

King Baby by Kate Beaton (Walker Books)

Kate Beaton’s The Princess and the Pony had many pleasures, but King Baby is even better. It falls in the "new baby" picture book genre, but what differentiates it is a very fine thing, in perspective and tone, that is carried off so deftly that the scenario and the conventions, social and narrative, that are involved feel immediate and fresh. There is fine cartooning to begin with but the shift of tone to something comically sinister with the pull-along duck incident opens the book out onto a sad, introspective consideration of love, independence and interdependence before the inevitable but nonetheless satisfying denouement. That sounds serious, but this book is innately funny and is pulling off an impressive acrobatic feat.

Owl Bat Bat Owl by Marie-Louise Fitzpatrick (Walker Books)

A family of owls and a family of bats begrudgingly share a branch until something happens to shake them both up. This charming book is entirely wordless and focuses on the same tree branch for its duration. This allows Marie-Louise Fitzpatrick to focus on the expressive quality of her animal characters and changes in environment to tell her story. The vibrant, graphic quality of the paintings (which I think are digital) lend itself to both stylised expression and subtle colour changes, both of which draw the reader in. The wordless acting, for want of a better term, is even more inveigling as it requires the reader to build the story in step with each image. The final effect is one of eloquence, as both the central plot of the bats' and owls' relationship is clearly tied up alongside a complementary sub-plot involving a separated pair of spiders. This is a universal story, but one that seems particularly relevant today.

The Wolves of Currumpaw by William Grill (Flying Eye Books)

In The Wolves of Currumpaw, William Grill’s robust text and sensitive, ingenuous drawings, scores of them, weave a story larger than the initial inspiration of a series of historical wolf hunts. Through careful economy, stylisation and colour choice, Grill makes icons of the landscape and characters (human and otherwise); these enable a visual shorthand that can whip through a novelistic level of detail, cut straight to the dramatic core of the story he's telling, for it is truly a dramatic fictionalisation of people, animal and place, and crucially, allow him to imply a whole world beyond what is laid out on the page.

Colour and motion here have the emotional impact of more abstract forms of visual art, and I'm thinking particularly of Expressionism, while the iconographic element has a rich echo of primitive and folk art, which only plays into the type of story Grill is telling. Panels are used deftly to increase the detail of the story and control its pace, although I feel the book still errs more on the side of the picture book than the comic as these panels also offer up a sense of simultaneity; of composite pictures.

I'd say of all the fiction books mentioned here, this is for the oldest reader, say 7 up, for the length and complexity of the story and the attention its telling demands. I haven't seen anyone use quite the same form as Grill is employing here and it's refreshing and satisfying.

This Is Not A Book by Jean Jullien (Phaidon)

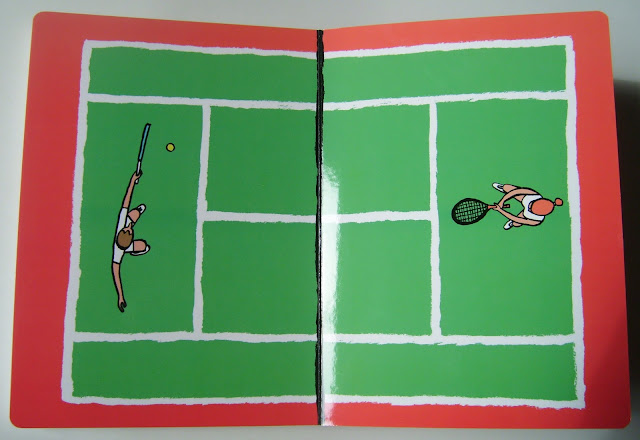

With each spread this book is not a book, it's something else: a laptop, a tennis court, a tent. Each has been carefully considered and economically, characterfully illustrated by Jean Jullien (a man who has cracked me up with just the image of an owl pretending to be a sheep). This transformation at every turn not only invites play, but also engagement on a conceptual level; binding what would otherwise be unrelated images together under the title of This Is Not A Book creates a coherent theme, on the object of the book and how its contents transform it. As a board book, the object becomes structurally robust and can be converted even further (wait until you get to the end). It's intelligent and an awful lot of fun, and I honestly can’t think of a better use for the medium of the board book.

We Found a Hat by Jon Klassen (Walker Books)

I don't want to say too much about We Found a Hat, because the joy of it is all in the telling. Jon Klassen is by now such an expert in colour palette, texture, composition and pacing that a reader is absorbed by the deceptive simplicity of the book and its many nuances work almost invisibly. I will say that it is the story of two tortoises (sorry Jon, turtles lives in the ocean) who encounter a ten-gallon hat sitting in the desert. They both think they'd look good in it. The dramatic tension is superb, and if you've read either I Want My Hat Back or This Is Not My Hat, you'll know how from such seemingly simple material Klassen can weave a story of considerable moral complexity. As a fan of those books, We Found a Hat also surprised me more than once. There is one particularly ambiguous thing it does that, taken literally, changes your perception of reality within the story to extraordinary effect. The bottom line is that the book is funny, surprising and challenging. The way it is told would be brave, if it weren’t so assured that it couldn’t possibly fail, and it doesn't.

Pandora by Victoria Turnbull (Frances Lincoln Children's Books)

Victoria Turnbull's third picture book (her second of the year) is to my mind her best. Pandora is an anthropomorphic fox-child who lives alone in a desolate landscape piled high with recognisable human detritus; alone, that is, until she cares for and befriends an injured bird. The text throughout the book is very sparing but well chosen; an awful lot is communicated by the images, which typically fill spreads either with panoramic detail or very careful and effective use of empty space. They are incredibly expressive.

The meticulous precision of draughtsmanship (I can't bring myself to use draughtspersonship, I apologise) in coloured pencil and graphite includes such control of posture and facial expression that Pandora's feelings are always clear. At the same time, that control gives us both incredibly subtle graduations of colour set against pitch black shadows and, while every line is precise, edges are soft. This visual scheme pitches the book in a rich, melancholic world that threatens both explosions of colour and unfathomable shadow, and travels between those poles. For, as simply as Pandora is structured, and as directly as the action is conveyed, there are many strands to the story. It is about good ecology, it is about friendship and loneliness, it resonates with the myth of Pandora; it is about hope. You could read it as being about depression; about intervention versus isolation. This richness of meaning and quality of execution makes it one of the most powerful picture books I've read.

There Is a Tribe of Kids by Lane Smith (Two Hoots)

A feral child, dressed in leaves, tries to find its place amongst various groups of animals, vegetables and minerals. The linguistic conceit to accompany this is listing their collective nouns, some I suspect common and some made-up. That could be the extent of the book, and in lesser hands, I'm sure probably would have been, but Lane Smith has a destination in mind and, while entertaining the reader with incredibly lively images, is crafting his meaning. There's so much energy, and also lightness of touch, in his deployment of colour, composition, pattern and sequential (comics) storytelling that you are carried through, without really being aware of the process, to a point of surprising self-realisation for the child. It's then that Smith's ultimate goal is revealled: he's stretched the linguistic motif as far as it will go, then twisted it back around to where it started, but the visual journey the reader has travelled has completely converted the meaning. It's a wonderfully effective example of keeping both the text and images in a picture book on separate registers to create meaning, in a work that is ultimately about belonging in a wide and wonderful world. And it's my favourite picture book of 2016.

Further Thoughts

To close out this post, I'd like to make a few honourable mentions and raise a few other thoughts.

Firstly, to recommend A Child of Books by Oliver Jeffers and Sam Winston (Walker Books).

I can't deny it's an incredibly accomplished piece of work, about the power of stories and specifically books. It works primarily on a poetic level, and the way this is carried typographically and pictorially throughout the work equally, constantly testing the line between the two forms of communication, is beautiful. But I can't help wondering if it isn't really aimed at adults, and designed and pitched from an adult's frame of reference. For example, to get the full effect of the use of existing texts graphically, you have to be familiar with these texts and their cultural significance, so while there is the potential for the book's meaning to grow with the child, it is immediately, retrospectively, complete for adults. This is really the only thing holding me back from a higher recommendation.

My second honourable mention is for A Brave Bear by Sean Taylor and Emily Hughes (Walker Books), which I dearly wish I could like better.

Suitably for a bear book, Sean Taylor (lest we forget, author of Hoot Owl) gets his script just right. The simple, allusive construction he's come up with (which is in essence really a poem), is rich material for a collaborator. Emily Hughes makes really attractive images, but I don't think as an illustrator she can sustain the journey this book needs to go through to become something extraordinary. To my eye, she misjudges some of the weighting of colour, tone and shape and compromises spatial awareness in the images (I can't read the illustration above as it is meant, for example). In overall book design as well, continuity and pacing are off; multiple images and additional vignettes hold up the pace of the text, when the story needs to flow like a river. There is no gradient to the sunset. I wrote in my original notes: "I can see the sun, but I don’t feel the heat." I would still recommend this book widely, I just don't think it reaches its potential. You can read about its creation in an interesting blog post here.

Thirdly, I want to say that the story of refugees in The Journey by Francesca Sanna (Flying Eye Books), while I have reservations about how well suited the text is to such eloquent imagery and if the narrative resolves itself adequately, is such an important work to get before the eyes of children at this time that there's no way I could go without recommending it. It needs to be read and understood.

I also wanted to give a mention to publishers here, as Walker Books and Flying Eye reliably published many fine books in 2016 and deserve due praise. I think Templar warrants consideration for publishing Kings of the Castle (above), and A River by Marc Martin, both a big step up in quality compared to any of the Templar titles I reviewed in 2015.

And then, back to the Caldecott Medal and Honors. All the books I've written about here, and thirty-two besides, I borrowed from my local library service. I think one of the prerogatives of the Caldecott judges is to champion books that might otherwise pass without recognition, because I find it hard to believe, for example, that There Is A Tribe of Kids did not pass through their hands, nor that it can be so much less accomplished a work than the five they have honoured for it not to be considered in the same company.

I've also been reading a lot of Dr. Seuss lately, and I'm amazed to think that in his long and distinguished career, none of his books were ever awarded the Medal. Three of his earlier books, McElligot's Pool from 1948, Bartholomew and the Oobleck from 1950 and If I Ran the Zoo from 1951, received Honors and then he was never awarded (by Caldecott) again, but became, as a creator of picture books, a household name.

I have no problem with singling out worthwhile books that would otherwise receive less attention, but it means they are much less likely to end up in a public library in the UK on publication, and that's why none of the Caldecott books appear on this list. I had not heard of four of them (I was hoping to have read Du Iz Tak?) and only one (They All Saw a Cat) is currently held by my library. I have a reservation for that one copy and I'm looking forward to reading it. What this also means, of course, is that the Caldecott list of "most distinguished" picture books is no more definitive than the one I have published here. So I encourage one and all to keep looking, keep reading and keep finding your own treasure.

Best wishes,

Luke.

No comments:

Post a Comment